Earthbag Diaries 3: Building our brand new home, one bag at a time

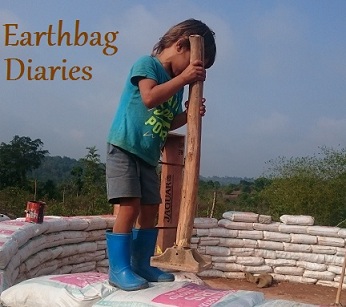

Requiring no special equipment and no special expertise, and very economical to boot, earthbagging is famous as an ‘idiot-proof’ technique, popular with first-and-only-time owner-builders the world over. Venetia Kotamraju, who moved from busy Bangalore to a farm on the Western Ghats, writes on her experiment with earthbagging. The third installment in a series of four.

Venetia Kotamraju, Ecologise

READ:

Earthbag Diaries 1: Stomping mud in Sakleshpur

Earthbag Diaries 2: Planning, material and equipment

Jelly Bags

Once the foundation is ready, you can start laying the first bags. We initially do three to four courses of jelly or gravel bags. These prevent moisture seeping up from the ground and into the mud walls. We don’t add any moisture or vapour barrier between the jelly and the mud bags.

Our tried and tested method for the jelly bags goes something like this:

create double bags (the jelly bags rely exclusively on the bag to maintain their shape, unlike the mud ones which cure and hold their shape, so need to be doubly strong) by putting one bag into another

lock the corners of the bag with a nail

turn the double bag inside out to create nice neat corners

fill with two bucket loads of small gravel (here affectionately called ‘baby jelly’)

tie shut with a thin wire

lug into place

tamp a bit but not too much or the bags tend to split

add two rows of barbed wire and repeat

You can get away with not nailing and inverting the bags of the first course – especially if it is partially or completely below ground level – because it won’t be plastered. If you don’t create these neat rounded corners for the other bags though, plastering becomes very difficult as you have big floppy corner flaps.

Mud Bags

The real fun starts with the mud bags.

The first thing is to ensure that the soil you intend to use has roughly the right proportion of clay, silt and sand. We did the ball test, the cigar test, the plate test and so on and so on. We found the most useful to be the simple jar test: fill a transparent jar with some subsoil (never build with topsoil, it’s a waste of fertile earth and the organic matter it contains isn’t good for building with), add about double the amount of water and then let it sit undisturbed on a level surface for a day. Check after 24 hours and then try to work out the proportions of sand, silt and clay by measuring the levels in the jar.

The ideal soil type for construction is no more than 30% clay. If you want to get really technical, you can read up on the difference between expansive and non-expansive clays. You can stabilise your soil mix as needed, by adding more sand, or more clay, or even some cement. Our soil is about 30% clay and we have always used it as is. My guess is that once the bags are knitted together with barbed wire and plaster, they are pretty stable whatever the mix.

Indeed, we have latterly realised that our soil mix last year was at times wrong. Several bags were filled but not used, and after being in the sun for a few months, the bags disintegrated. In some bags, the soil then simply crumbled apart, and in others it remained rock hard and kept its bag shape even in the absence of the bag. It may well be that the bags that form our walls contain some of the former crumbly mix, but thankfully, no signs of catastrophe yet.

Still, it is obviously preferable to have a mix which cures strong and hard, so after doing your soil test it’s worth filling a few test bags and leaving them to dry in the shade for a week or so, and then checking how hard they are. You should be able to hammer a nail into them and have it hold there as it would in a regular wall. And for off-roaders, I’ve seen photos of people testing the strength of a cured earthbag by driving over it.

The more crucial aspect seems to be how much water you use and how you mix it. Most people recommend 10%, which you can estimate by taking some mud, forming it into a ball and dropping it from shoulder height. The ball should shatter slightly when it hits the ground. If it retains its shape it is too dry – less than 10% water. If it shatters completely, it’s too wet – more than 10% water.

I think our mix last year was very often too dry. This is partly because it’s incredibly hard work to mix dry soil thoroughly with water using a gudli, and packing the bags is easier with a slightly drier mix. We unwittingly failed to monitor the moisture content of the mix throughout the construction and I’m guessing it gradually became drier and drier.

This year, to solve this issue, we have created massive earth pits into which we’ve piped a lot of water from the kere. We have then let the water sit for several days to percolate down into the pile. Once the water disappears from the top of the pit, you can dig up the nice gooey mud and store it under tarpaulins until you’re ready to use. You thus get ready-mixed mud which hopefully you can pack as is, or perhaps tweak a little – slightly more water, slightly more dry soil. You also get a great temporary mud pool for children and dogs to cool off in the summer heat…

As you can see from this photo, you need a fair bit of mud for the wall-building and plastering. I have heard of people who dig up the soil as they build but the building season here is also the dry season , for obvious reasons, and the ground is very, very hard. It would really slow things down (and possibly cause a revolt) if we dug up the soil manually so, destructive as they can be, we prefer to use a JCB for this and also the levelling of the site.

Another mistake we made last year was to fill the bags near the mud-mixing point, rather than in situ on the wall. All the resources I consulted advised filling the bags on the wall, but somehow we as a team found it easier to prepare the bags (nail the corners, fill, tie the tops) on one side and then pile them up for the strongest among us to heave onto the walls.

What happened at times was that we prepared tens of bags but didn’t put them straight onto the wall. A festival would then intervene and by the time the bags were laid on the walls several days had passed and they had already started to cure. This is one reason I wouldn’t recommend this method. Another is that as you get higher up, lifting the bags onto the wall requires some real strength, and several men. Drier bags are lighter and perhaps that’s another reason why our mix kept getting drier. This time round we are following the method outlined in Earthbag Building:

place the metal slider on the wall to protect the bag to be filled from the barbed wire underneath it

place the bag holder on top of this

add enough mud to fill the bottom and pack into the corners

diddle the bag, as they call it – ie: tuck the bottom of the bags in (almost everyone else suggests you do this with nails but the method this book uses does away with the need for nails except in exposed bags; this saves time and also money)

keep filling and packing the corners

finally seal the bag with a single nail (rather than the time consuming wire-stitching) and plop into place right next to its neighbour, top to tail (rather than top to top as others recommend)

tamp until level

lay two rows of barbed wire and then start the next course

Rather than measuring the mud as it goes in (eg: two bucket loads), the authors recommend filling the bag to a certain height (eg: 10 inches from the top seam). In our experience though, it is difficult to get similar sized bags that way because it depends on how far they bulge out horizontally as you fill them. So we prefer to go with a set amount of mud per bag – five small buckets – and then try to ensure that we seal the bags at the same point for a uniform shape.

Windows, Doors, Shelves, Drainage Pipes

Earthbag walls cannot easily be nailed or cut into as brick and mortar can. So you need to add inlet and outlet pipes for plumbing and electricals, as well as fittings for shelves, in-built furniture, doors and windows. And it is also worth including false doors – doorways filled with dry bags and then plastered over, which can later on be dismantled – if you think you might want to add an extension next year because you don’t want to have to carve a doorway out of an earthbag wall.

Work out well in advance where you want any openings to be and be ready with the placeholders and forms. We ended up having to try and lift about three courses of bags at one point, because we had forgotten to add a drainage pipe.

Doors and windows are a challenge. Last year we attempted to build a wooden door placeholder, only to find that it couldn’t handle the pressure from the walls, especially as the walls were unfortunately not plumb. Many people recommend building custom-made wooden forms for your doors and windows but we have no access to a local carpenter (the nearest one is in Sakleshpur) and wood here is expensive.

So this year instead we tried different ways of supporting the doorways as they go up. First was cement blocks, but those we found were too narrow – you need something which is at least a couple of inches wider than your wall so that you can get it out later; once the bags are tamped and pushed down from the courses above they will lock a narrow form in. Then we tried laying jelly bags cross-wise. That gave us the width we needed, but they didn’t brace the walls well enough and nor did they present a straight edge. We thus ended up with neat earthbag courses which became droopy and jagged at every door opening.

In the end, we gave up and found a wonderful carpenter who made three reinforced door-frames within a day. We then re-did the bags at the door openings to bring them right up against the doorframe.

We really wanted to build arched doorways but struggled with the height. If you build a simple arched doorway, you need the bottom of the arch to be at least 6.5 ft to keep tall visitors from having to duck. On top of that you then have 1 ft tall bags forming the arch, and then another two courses of bags minimum. And if you want to iron out the bump the arch creates in the wall, then you need several more courses. That brings you up to about 9 or 10 ft, which is huge and would of course mean walls that take a lot longer to build. If you are thinking of doing an arch above a regular rectangular door with a lintel, then the wall height would be even greater. Forced to abandon this idea, we consoled ourselves with arched windows instead.

Thankfully, this time we went straight to the carpenter and, after several hours in his workshop, ended up with a perfect arch form as well as a special tool to shape the fan bags that form the arch. We did a test on the ground, and, amazed and much encouraged when that held up, proceeded to build our arch windows. We followed, to the letter, the instructions for the entire arch building – from form to procedure – in Earthbag Building:

nail a 1 inch thick plywood sheet the same dimensions as the base of your arch form onto the wall

onto that mount your arch form

drive in wedges (so that you can get the arch form out at the end) and then level and plumb the form

create the special fan bags using the mould tool and place them one on either side as you work your way up

when you have a gap of less than eight inches at the top of the arch, half fill three bags in the mould and place them all together into the gap

carefully fill these three bags with the same amount of mud simultaneously until they reach the right height; then seal

add two more rows of regular earthbags to secure the structure

remove the wedges, let the form drop down and then pull it out

ta-da, you have a self-supporting arch

For attaching doors and shelves, someone thankfully invented what Earthbag Building calls strip plates, small pieces of wood which you nail into the walls as you build and which give you a wooden surface onto which you can attach wooden door frames and shelves.

You can also attach shelf brackets directly into these strip plates as you build.

Again, you need to have everything planned out very precisely so you don’t miss the right spot as the walls rise. And also ensure that your door, arch and window forms, shelves and anything else you’re attaching to or integrating into the walls are level, plumb and sitting in the wall as they should. Otherwise you will end up, as we have at various points, with undulating arches, leaning doors and sloping shelves – and quite possibly big structural issues as a result.

RELATED

Earthbag Diaries 1: Stomping mud in Sakleshpur

Earthbag Diaries 2: Planning, material and equipment